A mammoth undertaking

During the second week of October 2019, 30 EOU students and three faculty members spent four very long days outside of Prineville, Oregon, excavating a partial mammoth skeleton from a gravel quarry. The site was owned by late EOU alumnus Craig Woodward, ’69, who decided to donate the fossils to his alma mater.

Woodward passed away shortly after construction workers uncovered the fossils, but members of his family carried his enthusiasm forward. They worked with university leaders and faculty to make this final donation official with a memorandum of understanding.

Workers from Knife River Corporation had leased the land to extract sand and gravel, when they uncovered tusks about 30 feet below the surface. EOU students and faculty members from the anthropology and biology departments collaborated with construction crews to carefully remove the bones.

Anthropology professor Rory Becker said students in his introduc-tory classes got a first-hand look at archeology in action.

“I think a lot of the students were surprised at how much work was involved,” he said. “It takes coordination of many, many moving parts — plus, straight digging holes.”

For many of them, Becker said, it was a chance to decide whether fieldwork would be a suitable career path. The team’s 12-hour days from Oct. 9 to 13 often began and ended in the dark.

Becker led the dig with fellow anthropology professor Linda Reed-Jerofke and biology professor Joe Corsini. All three agreed that the experience offered once-in-a-lifetime opportunities for EOU students.

“The students were working hard, talking about their ideas, leading their peers,” Corsini said. “They were all excited to get out there.”

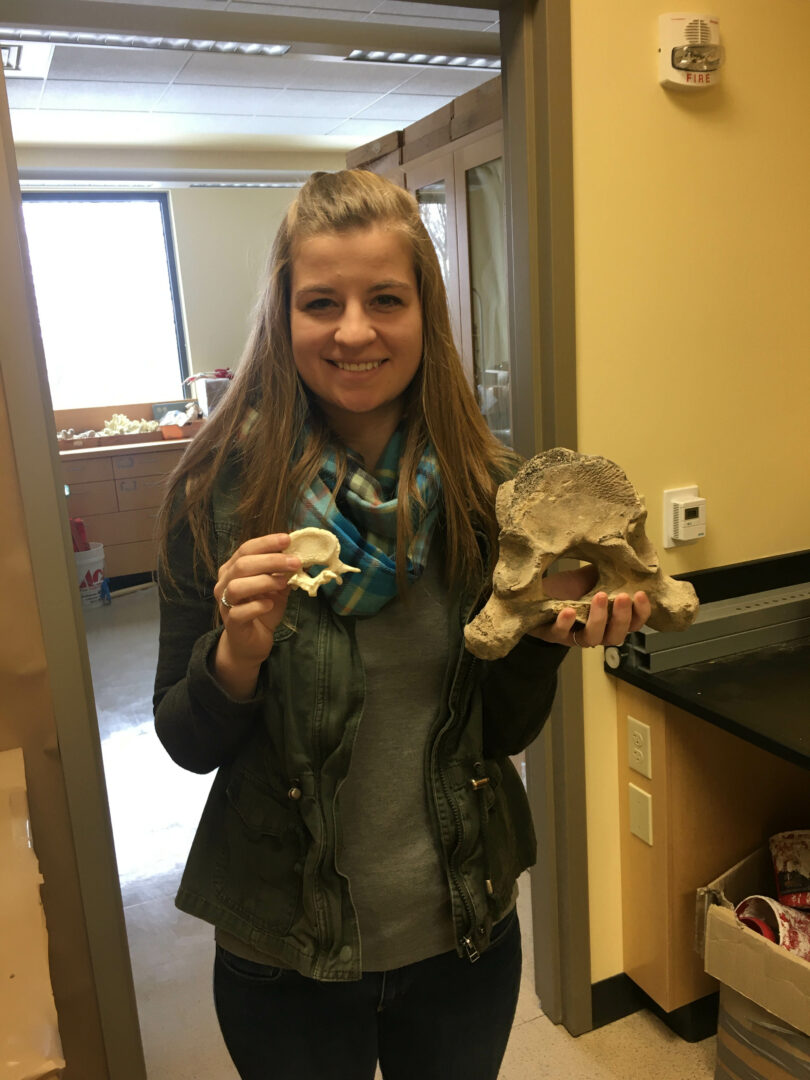

Students from three anthropology courses helped remove giant arm bones, including the ulna, radius and humerus, as well as tusks, a cranium and several vertebrae. Becker and Corsini said they suspect the mammoth may have been a juvenile because the ends of the long bones don’t appear to be fused to the shaft.

“The type of sediment surrounding it suggests that it may have been in slow-moving water,” Corsini said.

He was surprised that they didn’t encounter an assemblage of other fossils, such as camels, sloths, bison, and rodents, near the larger mammoth bones.

Mammoths and mastodons both roamed North America about 2 million years ago, and the last of these creatures died out on the continent 10,000 years ago. Eons of sediment and pressure had preserved the bones, so exposing them to air made, particularly the tusks, vulnerable to delamination.

To protect them, the team removed the bones packed in sediment, covered them in plaster, and transported them to campus on a flatbed truck. Corsini, an experienced paleontologist, worked quickly with super glue at the site to stabilize the tusks. All of the elements are now securely stored adjacent to biology and anthropology labs on campus.

“It’s a load of work,” he said. “Getting them back [to campus] intact is the biggest challenge and achievement.”

It also means that smaller bones like teeth and fingers might still be enclosed within the larger sections. Teeth could clarify whether the find is actually a mastodon, and reveal details about the animal’s diet.

Becker said the find will provide three to five years of research papers, conference presentations and capstone projects for EOU students.

“We anticipate enduring opportunities for student contact with the bones,” Becker said. “Far beyond the 30 students who helped dig them out.”

Eventually, they hope to display the remains for visitors to see. The partial skeleton means that an exhibit might be set up to recreate the dig scene. Corsini said he looks forward to sharing the find with students and the community.

“It’s always amazing to see something like that — this huge creature that’s no longer on the planet,” he said. “I always feel a little bit of awe.”

Q&A with student participants

Erin Blincoe is a junior from Baker City, Ore., studying anthropology.

My role on the dig: I was in the upper division class, so I helped oversee some of the other students.

What surprised me: I love working with bones. It was a salvation dig, so it wasn’t a typical dig. We had four days to get everything out of the ground, so it was speedy.

What I learned: I never thought of myself as a leader, but I’m very patient and that worked.

Lydia Hurty is a senior from Stanfield, Ore., studying anthropology and sociology.

My role on the dig: I did all the photo documentation, the shots with a clipboard showing where bones were found.

What surprised me: I got to go around to every item that we found. It was surprising to see the size of it!

What I learned: The ins and outs of what you do on a dig, and watching all the processes that go into it was really informative.

Christopher Smith is a sophomore from La Grande studying anthropology and sociology.

My role on the dig: I have kids, so I couldn’t go on the dig, but we’ve been helping remove sediment from the cranium now that it’s back on campus.

What surprised me: The bones are very brittle after they’re exposed to air. They’re about the texture and fragility of balsa wood. I’d never thought of fossils as being that brittle.

What I learned: In the classroom you get an idea of what you’re about to encounter, but it’s really cool to actually dig in the dirt.

Hannah Wilhelm is a junior from La Grande studying anthropology.

My role on the dig: I did a lot of plastering, covering the bones in plastic and wet newspaper after they were pedestalled.

What surprised me: It was really cool to be near this animal that’s been in the ground for 10,000 years. It takes you to a different time.

What I learned: Taking what I learned in the classroom and seeing it actually happening helped me realize that I want to focus on paleoanthropology.